Mobility Matters Extra - Is investing in electric vehicles socially regressive?

This is the second in a weekly set of deep-dive articles into transport issues and matters of interest to transport professionals. This is being made free to view for everyone as a trial run of this exclusive content. If you like it, sign up to become a paid subscriber, and you will get priority and exclusive access to content similar to this.

From next week, this type of content will only be available for paid subscribers. To avoid missing out on this content in the future, sign up for a paid subscription.

Key points

Current electric vehicle fiscal policy is socially regressive, mainly due to it potentially subsidising an increase in total vehicle trips;

Greater electric vehicle use is likely to lower overall transport emissions, that is more likely to benefit those on lower incomes;

Policy responses to this issue include a reverse sliding scale for electric vehicle ownership grants, prioritising electric vehicle charging points being installed in the road and in lower income areas, and implementing policies to reduce total vehicle trips.

Why this is a challenge

In the week where it was announced that we could see the first country in the world achieving 100% of new cars being electric or hybrid vehicles (take a wild guess which one it is), a question about the pursuit of electric vehicles rears itself. Is the pursuit of electric vehicles a socially-regressive policy? And consequently, should we then as transport professionals being spending our time and resources to help this revolution happen?

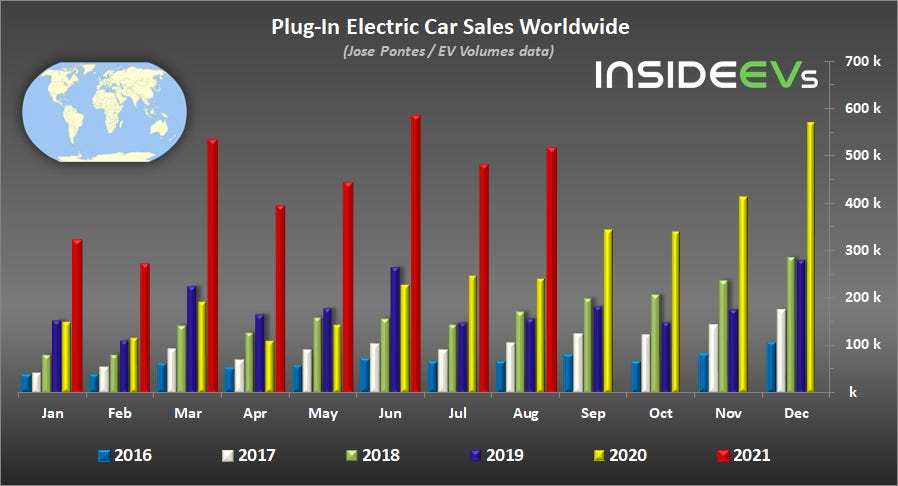

To put some statistics on it, the sale of electric vehicles has been on a scorching run in 2021. Data from Inside EVs has shown that monthly sales of electric vehicles have exceeded 500k vehicles globally for the last 3 months for which data is available, and could soon represent 10% of all vehicle sales globally.

Data on public sector support for electric vehicles in terms of tax breaks, funding for public charging infrastructure, and grants for vehicle purchase is somewhat more difficult to come by. In fact, without undertaking a Freedom of Information request, it is difficult to analyse in more detail.

In this post, what I hope to due to explain more about the 3 main arguments put forward as to why supporting electric vehicles is a socially regressive policy, namely:

People who are on middle and higher incomes will benefit disproportionately from both subsidies to stimulate electric vehicle uptake, and the lower costs associated with such vehicles;

Those who will experience the negative externalities of electric vehicles are the most vulnerable groups in society;

Electric vehicles are a manifestation of an historic battle that pits people against vehicles, but with fewer tailpipe emissions.

I will then conclude with some analysis of my own using UK data to attempt to show links between adoption of low emission vehicles and degrees of deprivation.

Do those on higher incomes benefit the most from electric vehicle subsidies?

An analysis of some of the initial evidence by Ian Irvine at Concordia University in Montreal would appear to indicate that being so. Citing another study into energy tax credits, Irvine suggests that.

The bottom three income quintiles have received about 10% of all credits,

while the top quintile has received about 60%. The most extreme is the program aimed at electric vehicles, and that the top income quintile has received about 90% of all credits.

But what Irvine’s initial analysis adds is interesting. It states that as the shift in the electric vehicle market moves towards more luxury brands, tax credits aimed at stimulating the market becomes more regressive. With the continuing growth of the Tesla Model 3, and even smaller electric vehicles hardly being on the affordability side of the spectrum, this sort of trend is hardly likely to slow down any time soon.

More interesting, however, is a recent study by Guo and Kontou. Whilst they confirm preceding analyses by stating that those taking up such subsidies had been in higher income brackets, the effects of an income cap in terms of subsidy qualification started to have an effect.

We find that rebates have been predominantly given to high income electric vehicle buyers. However, the share of rebates distributed to low-income groups and disadvantaged communities increased over time and after an income-cap policy was put into effect. Spatial analysis shows high spatial clustering effects and rebates concentration in major metropolitan regions.

A matter often commented upon is the second-hand vehicle market. This simply states that the purchase price of entry-level electric vehicles will be more accessible to those on lower incomes purely due to more second hand electric vehicles coming onto the market. As the market really doesn’t exist yet, there isn’t any good analysis of whether this claim is true. Furthermore, I would counter this with 3 factors that would affect the viability of the second hand market:

Batteries. Older vehicles will have older and near life-expired batteries. Whilst this is likely to further depress the purchase costs of electric vehicles in the second-hand market, battery replacements are far from cheap.

The ability to fix it yourself. One of the good things about combustion engine vehicles is that you can fix them yourself with standard parts and tools. Without a right to repair, that may not happen with electric vehicles.

Disposal costs. Simply, few know who will carry this cost. Particularly the costs of disposing of those troublesome batteries.

Regardless, this does not affect electric vehicle tax policy, for which there is clear evidence that it is very socially regressive.

Will the most vulnerable experience the negative externalities of electric vehicles the most?

The evidence on this appears to be overwhelming when you study the impacts of the current highway system and the associated supporting systems. This analysis shows that:

The poorest in society are the most likely to live in areas that suffer pollution issues

Vulnerable groups are the most negatively impacted by road traffic safety

To name but a few potential impacts. Let’s be clear here, the impacts of this are not particularly good, and the early evidence is troubling. However, this is a market that is emerging, and so the mature market may not necessarily reflect a market at its early stages. So let’s look at a couple counter-factuals.

The first is obvious - reducing tailpipe emissions. Emissions lifecycle analyses have been extensive and often controversial. There are a lot of opinions on it, that’s for sure. But the emerging consensus seems to be that the effect on emissions of electric vehicle adoption is likely to reduce overall emissions from vehicles, and may even be a critical first step to deeper emission reductions. The excellent Carbon Brief paints a good example of the Nissan Leaf:

In the UK in 2019, the lifetime emissions per kilometre of driving a Nissan Leaf EV were about three times lower than for the average conventional car, even before accounting for the falling carbon intensity of electricity generation during the car’s lifetime.

Electric vehicles do not solve all of the problems associated with emissions from road traffic that will affect people living close to busy roads. But their impact on local air quality and emissions is positive overall.

The second is less so - how the supply chain will change. Gunther et al have undertaken some interesting theoretical work on how sustainability could be installed throughout automotive supply chains as they are established through the adoption of electric vehicles. Their scenario work is very important as there are many factors that will affect how these new supply chains are formulated, such as government regulation, tax incentives, and technology adoption.

This touches upon an important point to consider - the existing electric vehicle supply chain may not necessarily be one that becomes predominant in the future. It exists now in locations where raw materials are easily available, and unfortunately exploitable.

In summary, the evidence for this claim is less well defined, and relies on being honest about assumptions of the future state. In a world where electric vehicles are an intrinsic part of a green economy, their externalities are certainly lessened. But the current world projected forward? There is no change. Take your pick.

And yes, before you say it, I know that a lot of places use coal to generate electricity. It doesn’t mean they will in the future.

The historic battle in a new context

The argument that electric vehicles are essentially a rehash of previous street battles, but this time with electric vehicles is as much philosophical as it is evidence led. It does make for some excellent content on Twitter, though:

Though to be fair, there is a point to this. The Energy Savings Trust recommends using build outs and even lamp post charging points where possible, and maintaining a 1.5 metre width on footways has a significant accessibility benefit for those with more limited mobility.

A further, and potentially more significant, point is that through significantly reducing the costs of travel, more people will simply drive their electric vehicles because it is so cheap. An initial study on early electric vehicle adopters undertaken by Rolim et al showed that:

Results indicate that the adoption of the EV impacted everyday routines on 36% of the participants and 73% observed changes on their driving style.

Although there is some worrying evidence emerging from a study of electric vehicle owners in Stockholm by Longbrook et al:

EV users make significantly more trips than their non-EV using counterparts, according to their one-day travel diaries and controlling for socio-economic and situational variables…[also] EV users choose the car for a significantly larger percentage of their total travel distance than conventional vehicle users.

Coventional transport economic theory certainly suggests the same. That more electric vehicles will mean more trips, and these are likely to be by the wealthiest people in society first. But does such a link exist? And if so, how can we analyse where such trips are likely to emerge?

There was only one thing to do. Do the analysis myself.

An afternoon with Excel

So I gathered together the latest data (April 20211) from the UK Government on the number of Ultra Low Emission Vehicles registered by local authorities in England, their population, and their score on the Indicies of Multiple Deprivation (IMD). You can find all this data, and the links to the sources and the methodology notes associated with this data right here.

I should preface this with a warning about the data. The IMD data at a local authority level is…problematic. It gives a good overall indication of how deprived a Council area is, but this hides wild variability that is captured at the granular level in other IMD data, but lost at the local authority level. For instance, in the London Borough of Kensington and Chelsea you have some of the most affluent areas in the country alongside many of the most deprived. IMD data at a local authority level is a decent indicator of affluence, but only that.

That being said, lets dive into the analysis, and start off with the prevalence of Ultra Low Emission Vehicles.

This data indicates that there is a strong negative and potentially linear relationship between the IMD average score, and both total ULEV registrations and registrations per 100000 people. Although there are some notable outliers. Just checking the original data from the Department for Transport, the number of ULEV registrations in Stockport jumped from around 900 to over 30000 in a month.

In other words, there is some evidence that indicates that the more deprived an area is, the fewer ultra-low emission vehicles will be registered there.

Ok, but what about electric vehicle charging points and their prevalence in deprived areas?

A similar result. It appears that there is a negative and non-linear relationship between IMD Average Score and both total electric vehicle charging points and electric vehicle charging points per 1000 population. In other words, the less deprived an area, its probably more likely that there will be more electric vehicle charging points. But there are a few data points that are outliers - notably Westminster that has over 1000 electric vehicle charging points.

This did lead me to wonder whether there was a correlation between the number of electric vehicle charging points and the number of registrations of Ultra Low Emission Vehicles.

Again, the data shows that something, might be there, and that there may be a slight positive relationship between the two variables. But there is nothing certain.

So where does this leave us? To borrow a classic researcher phrase, it means that more research into the matter is needed

In conclusion

To summarise all of this, it appears that there is some evidence that indicates that under the current transport governance arrangements, electric vehicle policy is likely to be socially regressive. Whilst overall emissions are likely to be reduced (good), current taxation policy benefits those with higher incomes, and the great number of trips that are likely to result from the lower operational costs of electric vehicles will be regressive in their impacts.

If you are expecting some conclusions here as to whether or not supporting electric vehicles is a good thing, you will leave here disappointed. This analysis is by no means comprehensive enough to make such conclusions. However, there are several things that policy makers can do to reduce the socially-regressive impacts of adopting electric vehicles. These are as follows:

Where incentives are provided to encourage electric vehicle ownership, ensure that they are on a reverse sliding scale - higher for those on lower incomes, dropping to 0% for people on higher incomes;

Prioritise electric vehicle charging infrastructure installation in areas of the country with the lowest incomes;

Mandate that electric vehicle charging infrastructure be provided on the highway where it is provided on streets, even if this results in the loss of (non-disabled) parking spaces;

Persue alongside policy initiatives to reduce the total number of vehicle trips on the network.

I chose this data not because it is the latest, but because on 1st April 2021, the local authorities in Northamptonshire were abolished and replaced with two new unitaries - North Northamptonshire and West Northamptonshire. Rather than spend half an afternoon reworking Excel to account for this (not to mention having to figure out the boundaries of the new unitaries compared to the old district councils), I decided to just use data from April 2021