Mobility Matters Extra - Transport professionals as doctors

Some musings following a successful Mobility Camp

Key takeaways

Use tools such social mapping to understand who influences a policy area, and how different connections work and how they can be used to achieve your end goal

Spend time in developing deep relationships with key people who are part of your social map. Understand what motivates them and how you can help.

Take time to develop the skills to communicate what you do in a clear and respectful way, not just relying on the fact that you are an expert in your field to carry you through.

It all started in Glasgow

This article starts with a confession. I had planned to write about something completely different this week – that of the policy landscape for autonomous vehicles. You will still read that article next week, but this week I was inspired by the participants at Mobility Camp to write something completely different, and something often not written about by professionals who do transport planning and community engagement.

Many speak a lot about how we we engage with people, and the methods that we use to ‘secure buy-in’ and ‘co-design’ with people. We rarely – if ever – talk about the nature of the relationship that we as professionals have with the public, and what sort of relationship it should be.

So, as this train from Glasgow is speeding through the Scottish Lowlands, and with barely a few hours to articulate these thoughts, here we go.

Our relationship with the public

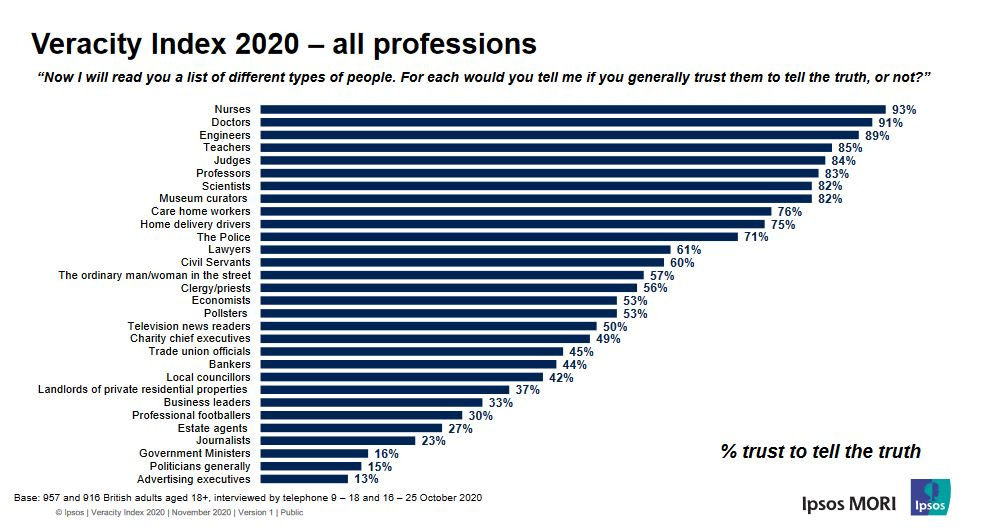

A fundamental question to ask is whether transport professionals actually have a relationship with the public at all? In the UK, IPSOS Mori have run the Veracity Index of trust in professionals since 1983. The answer to this question is the answer to the question “how do you classify transport professionals?” If its as engineers, it turns out that you are very much trusted – 89% of people generally trust you to tell the truth. If you are a civil servant its way lower – 57%, not much better than economists at 53%.

So, the overall picture you could argue is that the people generally trust us transport professionals to tell the truth. Which is a good place to start from – people trust us. But then the question I often hear at events comes forward, although I have slightly adapted it here. If people trust us to tell the truth, why do they resist our ideas for making places and streets better, more sustainable, and more just?

This has traditionally been looked at in terms of the engagement and participation methodologies we use, and how early in the process we engage with the public. Studies from places like the UK and Australia are just a couple of many, many works into the value of early stage and highly participatory approaches. At a personal level, I am very much an advocate of getting people involved early, and delivering co-design processes that put their needs at the heart of what we do.

It is also worthwhile remembering that no matter what we do, many will simply not be convinced of the value of what we are doing, and will fight tooth and nail against your plans and what you are trying to do. For example, 4% of people in the UK are not concerned at all about climate change, and so you cannot convince everyone of your point of view all the time.

But trust and how we communicate are only two parts of a relationship. They are incredibly important, obviously, and without either any relationship is doomed to fail. For a relationship to work and for both parties to achieve what they wish out of it, more than that is needed.

The transport planner will see you now, Mrs Jones

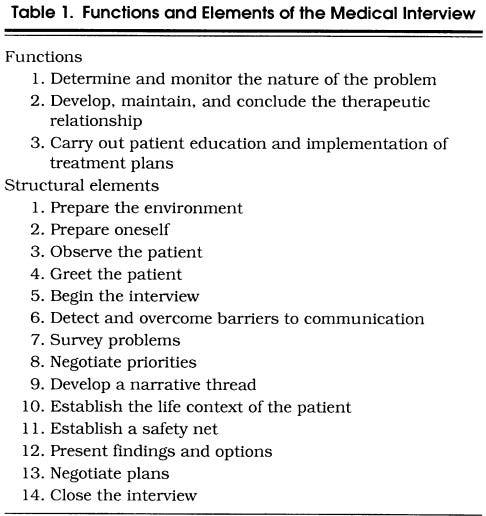

For some time now, I have been thinking about the value of probably the best known, and most trusted professional – public relationship that I can think of. That between a Doctor and their patient. Whilst there are aspects of that relationship that clearly do not apply (unless we want all transport planners to know of the medical records of everyone they talk to). A great article by Goold and Lipkin breaks down thousands of years of research into this relationship:

The interview has three functions and 14 structural elements. The three functions are gathering information, developing and maintaining a therapeutic relationship, and communicating information. These three functions inextricably interact. For example, a patient who does not trust or like the practitioner will not disclose complete information efficiently. A patient who is anxious will not comprehend information clearly. The relationship therefore directly determines the quality and completeness of information elicited and understood. It is the major influence on practitioner and patient satisfaction and thereby contributes to practice maintenance and prevention of practitioner burnout and turnover, and is the major determinant of compliance. Increasing data suggest that patients activated in the medical encounter to ask questions and to participate in their care do better biologically, in quality of life, and have higher satisfaction.

A critical part of the success of this approach is the time that Doctors spend, during their training, in understanding the importance of this relationship as their key diagnostic procedure, understanding the patients motivations and what can be done to ensure that they get the most out of this engagement, and understanding the science and psychology at play in this relationship.

Stern et al identify a number of practical actions that can be taken to mitigate different situations as they arise. But what is at the centre of this relationship is not only the degree of trust that the Doctor instils in their patient, but how through this the doctor and the patient work together to identify the most appropriate form of action, and work collectively to agree the best course of action to which both parties consent.

Now, I bet you are thinking that “well, us transport planners do that already! We work with people. We engage them as part of the design process, and so why should we do more?” Yes, we do a lot of that (mostly). But this misses the point somewhat. In such a situation, we are approaching these matters as people who assume trust is given because the other person is an expert. But why the doctor-patient relationship is so special is because it augments that with trust built on a more personal and deeper level. By making people feel that you are listening, that you are making them at ease, and then from there when you do recommend solutions that tackle the issue at hand, a deeper trust is established.

What I am not saying here is that all transport professionals need to have deep, personal relationships based on a high amount of trust with all whom we serve. That is clearly impossible to do – we serve everybody. What I am saying is that by having a deeper, meaningful relationship with a few key people in the communities that we serve, that trust can be replicated through numerous personal relationships and other people who also have those relationships with others in their local communities.

Relationships are not linear, they are webs

In Mobility Camp, we touched on this in one of our sessions on putting the pedestrian first. We undertook a Social Mapping exercise to identify who we as transport professionals need to start influencing in order to put the pedestrian first. We came up with this social map.

One of the key conclusions about this, which was ably summarised by my good friend Liani Castellares, was how centralised this process of winning people around was. In order to do projects, you needed to speak to people in turn and often at length to say that you have ‘done consultation.’ Our discussion then moved onto something more profound.

What if, assuming that this current system of influence isn’t working at putting pedestrians first, we started to work around this system? What if we started building and developing relationships with others who are influencing the people who we need to influence to get decisions made in a manner that changes the world.

On a more personal level, this diagram, created inside 15 minutes at the end of an unconference, led to a more profound realisation. What if part of the reason why we as transport professionals don’t get to enact change that our knowledge deems right not just because of where power and decision making lies, but because our way of attempting to change is to try to persuade or bludgeon our way through a system that ultimately wears us down? That means that change doesn’t happen, or only does after countless transport professionals have given up trying?

In concluding this, I must admit that my own thoughts on this are still developing and emerging. They are likely to change in the future, and as part of that I would love to hear your own perspective. I have no idea whether or not the doctor-patient relationship is a useful comparator, or whether it is feasible in the world of transport to achieve, but I do feel that it is worthy of further exploration.

Practical recommendations

What I can recommend that you as transport planners do is the following:

Use tools such social mapping to understand who influences a policy area, and how different connections work and how they can be used to achieve your end goal

Spend time in developing deep relationships with key people who are part of your social map. Understand what motivates them and how you can help.

Take time to develop the skills to communicate what you do in a clear and respectful way, not just relying on the fact that you are an expert in your field to carry you through.