Mobility Matters Extra - The state of autonomous vehicles policy globally

It's a jungle out there

Key points

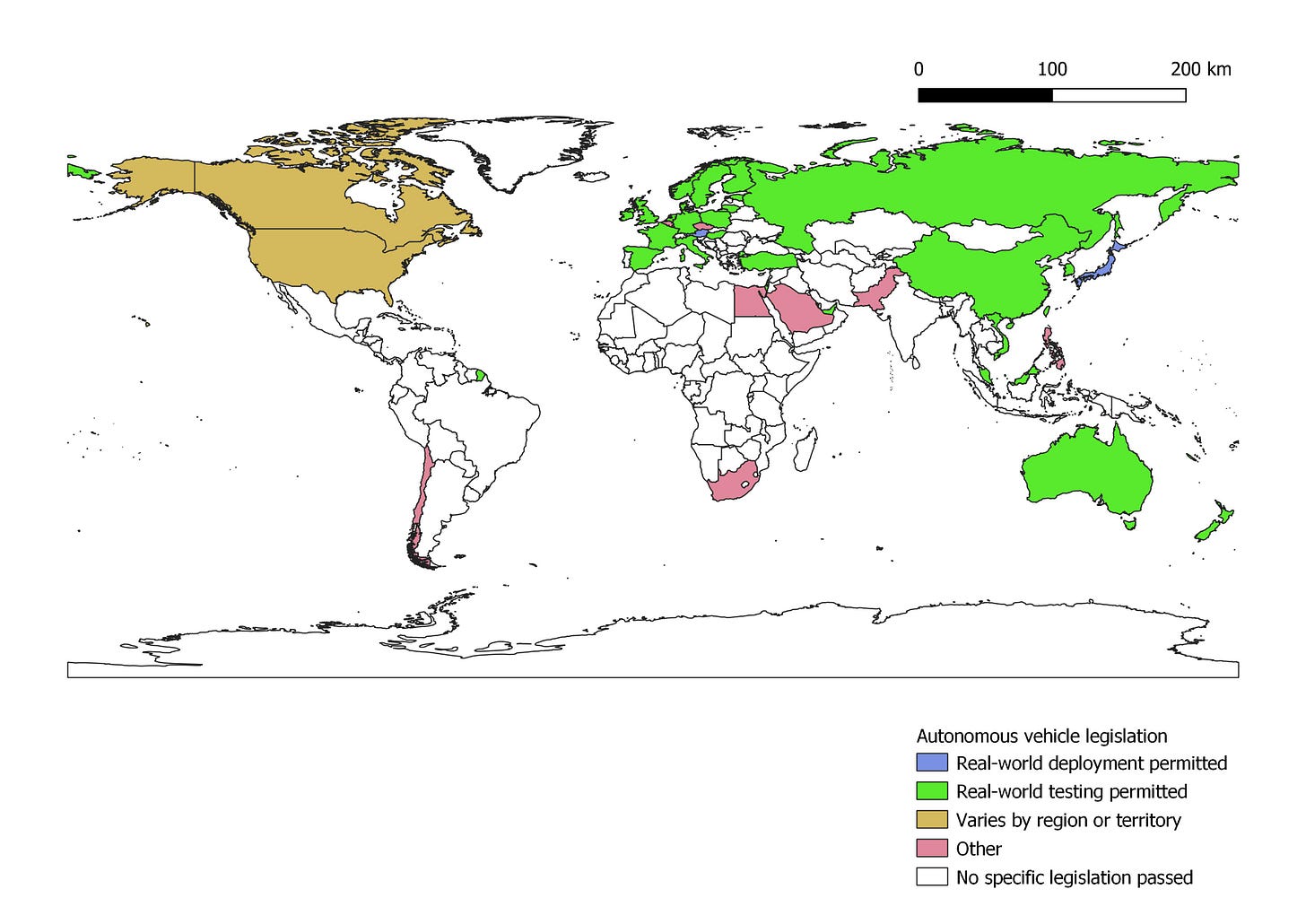

Current policy and legislation for autonomous vehicles is highly variable across the world

Determine the role of autonomous vehicles in delivering wider policy goals such as inequality and climate change

Commission research, based upon deep engagement with a variety of people, into how people see autonomous vehicles could make a difference in terms of tackling inequality, achieving net zero, and stimulating economic growth (and don’t just talk to industry)

Study carefully the impacts of legislative changes on reducing supply-side market barriers to autonomous vehicles. Adapt the key lessons into standards, legislation, and future policy.

Shift the autonomous vehicle debate from market opportunity, to market creation.

Yep, we haven’t spoken about it for a while have we

We haven’t heard from autonomous vehicles for a while, have we? The vehicles and their associated technologies are very much in their trough of disillusionment according to the Gartner hype cycle. To be expected in the development of any new technology as the technical limitations and use cases become much clearer. So it is easy to conclude at this stage that work has not been taking place to enable their ultimate roll-out.

Though I am sure that you are more intelligent than to think that. Just because something is not being announced at tech conferences or subject to numerous think-pieces in tech journals, doesn’t mean it is not happening. For example, whilst investment in autonomous vehicle companies has slowed compared to 2014-2017, there is uncertainty about whether this is due to the impact of COVID-19 or investors getting cold feet.

But an equally important aspect of work that is often not reported on is the policy and legislative environment changes that need to happen to enable autonomous vehicles to be deployed globally. This is what this post will provide a snapshot of.

My research method used

The ultimate question we need to answer here is simple: “Where have autonomous vehicles been legislated for, where is there a policy framework in place, and what does that framework focus on?”

The research method used here was a simple one: lots of coffee, Google Scholar, Google itself, lots of time reading websites and government documents, and QGIS. What I was looking for was details of legislative and policy changes that have taken place in countries across the world.

But to help refine the search, a few more things needed defining:

What level of autonomy is autonomous? Many of you will know about the 5 Levels of Autonomy. In defining whether or not a place has autonomous vehicle policy or legislation, the magic level I was looking for was at least Level 3 Autonomy.

Who is legislating and creating policy? For this, I researched two types of body: international standards bodies and national governments.

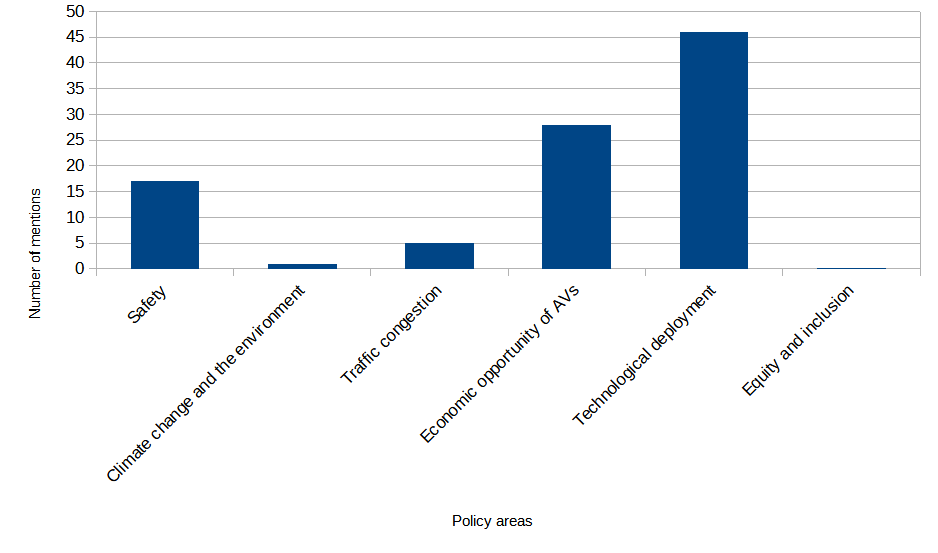

What policy priorities to look for? For this research, I searched for mentions of the following policy priorities within the policy documents and legislation; safety, climate change, traffic congestion, economic opportunity of autonomous vehicles, technological deployment, and equity and inclusion.

What geographical areas to look for? A surprisingly tricky question. Some countries that we may consider countries are not actually countries, and others we don’t consider countries are. Overseas territories muddy the water a lot in terms of legislation and policy, and I spent far too long trying to understand who actually sets policy in places like the British Indian Ocean Territory.

Despite this, there are a few caveats with this work. Firstly, just because a specific peice of policy or legislation on autonomous vehicles has not been passed, doesn’t mean that deploying autonomous vehicles is illegal in that nation. Secondly, even despite my research, my knowledge of the legislative environment of devolved administrations and territories within individual nations is limited to the knowledge of the internet. Thirdly, the country definitions used were those recognised by the United Nations. I am not going to get into debates on whether Taiwan or Hong Kong are countries, sorry.

The data

I created a spreadsheet containing a simply cross-tabs of each country, whether there are autonomous vehicle laws, what their policy priorities are, and links to further information. Also, the map I created is online.

Spreadsheet of countries and autonomous vehicle policies (.ODS spreadsheet)

Where you can deploy autonomous vehicles - map of countries (QGIS Cloud)

Where can you deploy autonomous vehicles?

In most countries in the world there is no law governing autonomous vehicles. Some countries, like India, are actively opposed to its deployment on the count of the potential loss of jobs. The majority of countries simply do not have autonomous vehicles as a policy priority, although Guernsey was the only one to actually articulate why (they don’t have the capacity or capability to do it).

Again, I should stress here that this does not mean that deploying autonomous vehicles in these countries is illegal. It just that there is no specific law that enables the testing of autonomous vehicles. The practice is highly variable from area to area, but several common themes emerge:

Where testing does take place, it is on private land or on test tracks that are not available to the public;

No testing generally takes place on the public highway, and;

There are usually specific laws governing driving that either make mention to a driver being at the wheel, or it is implied through case law in those nations.

There is also a notable north-south difference in legislation, with Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Malaysia and Singapore being the only nations south of the Equator who have formally legalised at least on road testing. Amongst those who have legalised on-road testing, the testing regime varies. There is often a need to formally seek a permit from a national regulatory body, which clarifies issues of liability, the testing regime to be used, and the location of the tests.

Almost all testing regimes require the human in the vehicle to be able to maintain control of the vehicle at all times, either as a passenger or more commonly by a trained driver.

For those countries where actual deployment is possible on public highways (basically Japan), commercial deployment is lacking. This is for reasons that I have been unable to research as part of this work.

Then we have North America, where the national governments of the United States and Canada have essentially said “yeah, you states and provinces go ahead, and if you need us we will help out.” The roles of federal governments have been more along the lines of guidance, common testing standards, and selling the capability of states to overseas investors. Meanwhile, practice at a state level is highly variable. Whereas California and Ontario are pressing ahead, others have been less than willing.

The Others are a real mixed bag of testing being permitted on private land (Egypt) to very specific areas in countries being permitted to deploy (Dubai, UAE).

What are the key policy drivers?

It’s deploying the tech and the economy, stupid. In nearly every country that mentioned autonomous vehicles as part of their policy initiatives, simply deploying the technology was mentioned as a policy goal. A significant number of them mentioned the economic opportunity of deploying autonomous vehicles in terms of investing in jobs and creating a new economic growth sector.

This shows the interesting position that autonomous vehicles are in for policy makers. At present, apart from a few isolated use cases, autonomous vehicles are not a realistic mass transport proposition yet. But they represent an economic opportunity.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying believe the predictions of huge values of the autonomous vehicle market in the future here. What I am instead referring to is the value of the constituent parts of the market which already exist. Think LiDAR, camera technology, machine learning, big data analytics, remote sensing equipment, and even the vehicles themselves. Those things exist now to varying degrees in many countries. Developing a new market for those component parts increases demand for them, which increases the number of jobs, which increases spending - you get the picture.

Autonomous vehicles are not a transport policy, and whilst their impacts will be in transport, it is incorrect to think of them as a transport policy issue only. They are as much, if not more, an economic policy issue, and how do countries and regions seize a slice of the economic pie before everyone else does.

How do you do that? You guessed it. By giving the right market conditions for these vehicles to get established and to flourish.

Oh sorry, did you expect me to say that they should be made road legal because that will enable the market? Yeah, I don’t know how to put this, that doesn’t enable a market. But the other policy priority areas do enable it. Let me explain.

Demand and supply side barriers to autonomous vehicles, and where policy goes from here

The focus to date of policy makers has been what they refer to as market enabling. At an international level, this has meant is working together on common standards. The European Union has been leading the work in this area by starting work to adopt common standards for permitting autonomous vehicles on European roads. SAE International have also commenced work on developing these standards, but the reality is that we are some way off common consensus at an international level with regards to standards for autonomous vehicles.

But allowing vehicles to test on public roads is an example of reducing supply-side barriers. Doing so, conventional economic theory tells us, will reduce costs, increase efficiencies and create a more dynamic market in the short term with new market entrants. They, in effect, reduce the costs of doing business. But as an emerging market, autonomous vehicles present one huge barrier: a lack of demand.

Businesses usually overcome this huge barrier in two ways. The first is quite literally having cash in the bank that you can burn through until the market catches up to your idea to the point where it is willing to pay an amount that covers its costs. Hence the focus of many companies on raising investment rounds or securing government-back research and development spend to maximise their burn time. The risk here is that the market becomes so used to your product being sold at under the market cost that raising prices becomes difficult if your demand profile is relatively elastic. See, for example, Uber.

The second is to focus on a specific use case that is easy to deploy and has an established value for an existing customer, to generate the revenue and profit whilst the more general consumer market catches up. An example of this is Oxbotica, best known for its autonomous vehicle trials, who are actually making quite a lot of money deploying their tech to support mining in reducing costs and accidents at mines. Tesla is also, arguably, an example of this and the former, with its ‘autonomous’ driving system essentially supporting what is now a highly profitable electric vehicle manufacturer.

To date, government policy has not focussed on stimulating the market because the technology is arguably not quite ready, but also because of a general laissez-faire approach to stimulating consumer demand that is endemic among policy makers. But the policy areas that have been paid attention to the least like safety and congestion are now beginning to be explored more meaningfully through research.

In the European Union, for example, recent Horizon 2020 calls have focussed on enabling research on the safety, reliability, and efficiency of autonomous systems. A notable example is safe operations in poor weather. UK research into people’s attitudes on autonomous vehicles reflect the importance of researching these questions:

People from all backgrounds had the same key questions.

Will it be safe?

Will it be available to all?

Who will be in control?

How do we get to a future with CAVs on the road?

This is the demand side currently at work. If government’s are serious about autonomous vehicles as an economic policy, they must now start considering autonomous vehicles as a demand policy. What trips will be substituted? How many trips by autonomous vehicles would be acceptable? How can the government support the emergence of the market through tax breaks and grants (e.g. electric vehicle ownership)? What is the impact on the job market?

These are questions for which there are no set answers yet. Even market forecasts for autonomous vehicles are based upon industry supply data, and so are prone to all sorts of errors in their assumptions about consumer demand. These questions are philosophical, and some stated preference work is probably required to gain an initial understanding. But at present, these are more questions of vision as opposed to questions that have a right or wrong answer.

Do we want autonomous vehicles?

You will have probably noticed I have avoided the big question: do we actually want autonomous vehicles? I would like you to come to your own conclusions on that particular question, but for now, I will give my own answer, and my logic behind it.

My answer is that it’s a pointless question. It’s pointless not because we have autonomous cars everywhere, but because the technology and its deployment is already happening. This particular genie is already out of the bottle, and whilst we could ban all autonomous vehicles now through legislation, we are only delaying the inevitable. This article by Our World in Data puts it well: when a technology is invented it in effect develops its own momentum that can be slowed, but not stopped.

So much of human progress has been based on technological improvements. The more important questions, therefore, are how do we deploy them to best tackle the issues that we as a species face, and to make a better world for everyone?

Conclusions

The current autonomous vehicle landscape is a patchwork quilt of supply side regulations and policies. Over the coming years, the policy focus needs to shift towards enabling the kind of market we want autonomous vehicles to be. So, here is what we as policy makers must start doing:

Determine the role of autonomous vehicles in delivering wider policy goals such as inequality and climate change

Commission research, based upon deep engagement with a variety of people, into how people see autonomous vehicles could make a difference in terms of tackling inequality, achieving net zero, and stimulating economic growth (and don’t just talk to industry)

Study carefully the impacts of legislative changes on reducing supply-side market barriers to autonomous vehicles. Adapt the key lessons into standards, legislation, and future policy.

Shift the autonomous vehicle debate from market opportunity, to market creation.