Mobility Matters Daily #80 - Removing highways, free public transport, and the politics of international transport

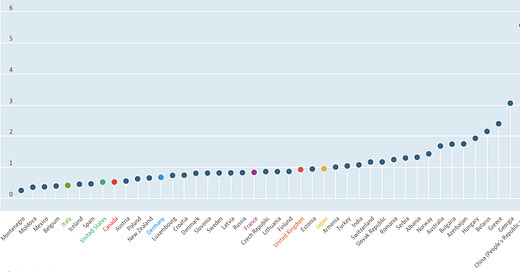

Today's graphic shows you quite how much China is investing in new infrastructure

Exploring different options for highway removal

An often-celebrated method of radically redesigning cities is the removal of heavily trafficked-roads, especially raised sections. This sort of intervention comes from valuing other aspects of development over movement, but interestingly research has shown that such works are seen as transport projects and are assessed as such, as opposed to providing a template for more radical change in a city. The history of highway construction in cities is that of segregation, so why not focus on their removal as desegregation?

The traditional highway response is creating a boulevard in place of the removed highway. But the discourse is very much around righting a previous wrong, as opposed to doing something better. An interesting alternative approach was applied in Rochester, New York, where part of the old ‘inner ring’ was removed for development. Three developments are now taking place on the almost six hectares of land freed up through removal, including a “Neighbourhood of Play.” Don’t just think removal, think renewal of cities.

Does free public transport work?

That’s a nice big question, but the policy idea is getting plenty of traction. For good reason. With concerns about regarding economic recovery, and getting people back onto public transport, as well as the increasing number of trials of the idea, it is gaining traction as a policy idea. The Green Party in the UK made free public transport part of their recent local election manifestos. But does it work? It depends on how you measure it.

In terms of more people using public transport, there is evidence that shows that it does just this. The impact on modal shift depends a lot on the level of public transport use that there was before free travel was in place. The impact on car travel in cities is minimal, and the impact on public sector spend varies according to how much fares covered the costs of operations originally. Ultimately, someone pays the cost of it all, but if you want more people to use public transport, it may not be such a bad idea.

The politics of international transport is far more interesting, and complex, than you think it is

The capture of Belarussian journalist Roman Protasevich, after his Ryanair flight from Athens in Greece to Vilnius in Lithuania was diverted to Minsk while flying through Belarus airspace, has caused a political uproar. Transport is often used as a football for political ends, but often in less obvious and more absurd ways.

The strong link between the development of air transport links and highly protectionist economic policies is well established, a good example being the Australian government banning airlines from Singapore from operating from Australia to the USA. Also, different operational requirements set by national politics (and carriers) holds back the expansion of liberalised access to international transport markets. Meanwhile, intiatives such as the New Silk Road have been studied as a ‘new world order.’ All of this is fascinating to a politics nerd like me, and goes to show how transport reflects the politics of the time as much as the society of the time.

Stat of the Day

When it comes to investing in infrastructure, as this data from the OECD shows, nobody does it like China. Over 5.5% of the GDP of China is invested in new road and rail projects. The UK, meanwhile, which has had the ‘biggest investment in [insert transport infrastructure here] for over 100 years’ for about 20 years, barely has 1% of its GDP invested.

Data link: OECD Dataset